Marcus is currently a Year 2 Student reading Physiotherapy at Singapore Institute of Technology. With 5 years of lifting under his belt, he contributed to the Powerlifting community by being the President of SIT Powerlifting for the year of 2020. Marcus once slammed his head so hard into a bar to psych himself up just to have it bled so much he went to the emergency department. He currently has an interest in Pain science, as well as making people stronger and healthier through the use of resistance training.

Disclaimer: This is not meant to be medical advice, please seek help from a qualified healthcare professional if you are injured.

Introduction

Jack is a powerlifter. He hasn’t been lifting for awhile due to COVID restrictions. After 4 long weeks, the restrictions have been lifted. He can’t wait to start lifting. Jack gets to the gym, hyped-up and ready to smash his workout. As he warms up for squats, he feels great. Nothing can go wrong right? As he takes his top set, he descends into the squat with confidence. Suddenly, as he explodes up, he feels a “pull” in his lower back and drops the bar on the safeties. Jack immediately feels a painful sensation around his lower back and lays on the floor. He sinks into despair, thinking to himself, “It’s over. I broke my back. I can’t lift again.”

Jack might be an example of a lifter who experiences a sudden injury and pain while lifting. Injuries happen even to the best of us and the experience of pain is normal. In fact, the experience of pain is important in warning our body of harm or potential harm that might occur. In this article, I will try and explain some basic pain science using my knowledge that I have garnered from my education and reading.

So What Is Pain?

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

This definition may sound simple and intuitive, but I would like to explain its nuances. Traditionally, pain is associated with some sort of identifiable bodily injury (Engel, 1977). I am sure many of you feel this way, “If I feel pain, I must be hurt!”. If you broke your arm, you would definitely feel pain. This is probably universal, unless you have a medical condition that makes you not feel pain. However, when it comes to a lifting related injury, is it really obvious that you “broke your back”? As with the definition of pain, “potential tissue damage” could be associated with the experience of pain. Experiencing back pain as you come out of the squat could very well be a defense mechanism of your body to prevent you from getting injured. But do we know for sure if something really did happen? We just can’t be certain unless we have supernatural x-ray vision. In fact, the relationship between pain and structural damage have come into question. Research suggests that even with identified structural damage, an individual might not experience pain (Barreto et al., 2019; Tonosu et al., 2017). Pain is complex and it requires us to look at it at different angles.

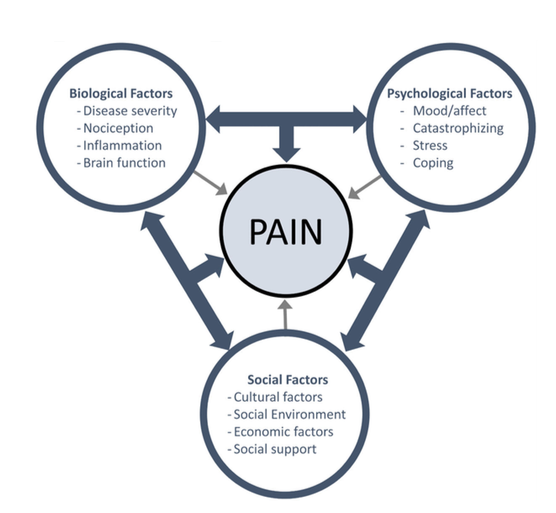

The modern view of pain is that there are various domains that can influence our experience of it. George Engel’s Biopsychosocial (BPS) model is a good way to represent a person’s pain experience holistically.

With reference to Figure 1, we can see that the experience of pain not only involves the affected body structure (biological factors), but also psychological and social factors. Hence, things like catastrophizing, fear, previous experiences and beliefs are just some of many factors that can influence a person’s pain experience.

Using our initial scenario as an example, we can identify psychological and social factors that might alter Jack’s experience of pain. Let’s say Jack has had many previous instances of “tweaking” his back on squats. Because of that, he had to take months off training just to recover. His journey to recovery was difficult and rocky. He was always trying to find a quick fix but it didn’t bode well for him. Furthermore, COVID has taken a toll on his mental health as he was deprived of lifting. His previous experiences and stressed-out state have led him to believe that the same thing will repeat itself. He catastrophizes, making him panic-stricken, doubting whether he can ever lift again.

With this background knowledge of Jack, what do you think his experience of pain would be? Looking at his history, we can postulate that his pain experience might be quite severe, with many psychosocial factors contributing.

What is the likely outcome after an injury?

Previously, we have discussed the multidimensional contributors to pain. The severity of an injury alone cannot account for the experience of pain. You might be wondering, what is then the usual course of pain and injuries? As with most injuries that involve musculoskeletal structures, and are not caused by significant trauma, the pain will subside as the body regenerates (IASP, 2009). Typically, the body optimises for recovery by adopting pain-avoiding and recuperative behaviors (Meulders, 2020). As the tissues get better, the pain subsides and the body would bias more towards returning to normalcy. So what does this mean for the typical reader? Likely, even without doing anything, the body will heal itself and the pain will go away in due time. So relish in the fact that your body has natural mechanisms to heal itself and don’t go catastrophizing if you had an injury. It would only serve to increase your pain experience and make the road to recovery longer.

So when is the pain bad?

Having discussed how pain is beneficial in the short term, when might pain be debilitating to an individual? Chronic pain is one such category that could cause an individual to be greatly affected by pain. Chronic pain can be said to be “pain that persists past normal healing time” (Treede et al., 2015). The average time for pain to be deemed chronic tends to be 3-6 months. Having chronic pain might indicate that pain has lost its beneficial role in protecting the body, and is now causing detriment to a person’s life (Cordier & Diers, 2018). Furthermore, there are a myriad of medical conditions that themselves cause the development of persistent disabling pain. These conditions affect how pain is produced and transmitted in the body, leading to symptoms of chronic pain.

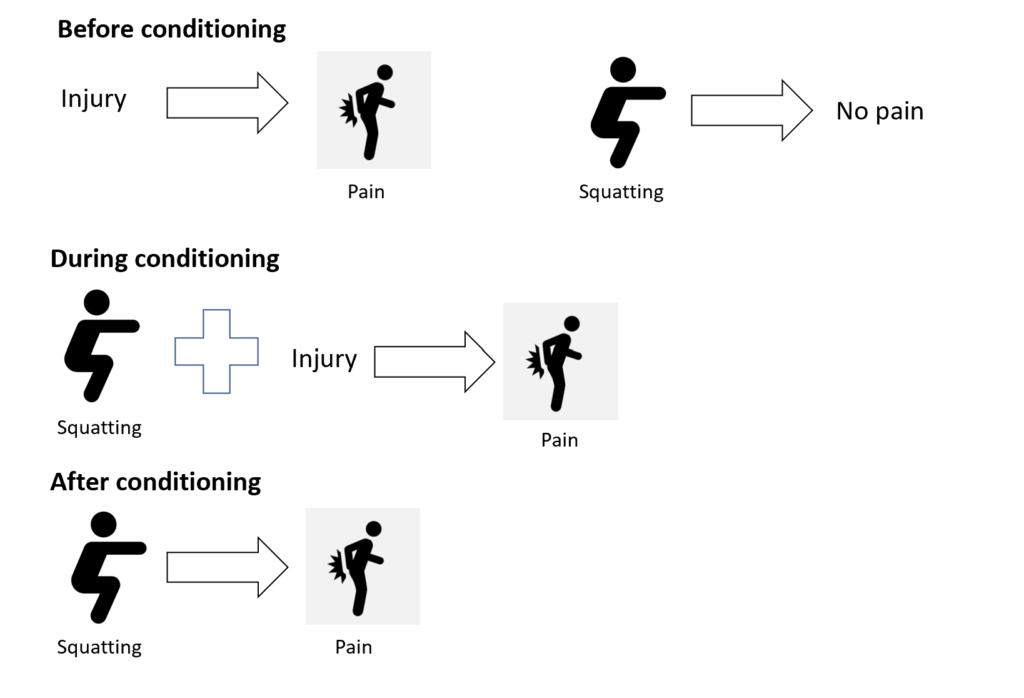

With regards to powerlifters, movement is an integral part of our sport. Our body has the ability to adapt to pain, causing an undesirable fear of movement. Classical conditioning or Pavlovian conditioning could be one such way our body learns and responds to pain (Cordier & Diers, 2018). Let’s use Jack as an example. Before Jack’s back injury, squatting was a pain-free exercise. But after his back “tweak”, everytime he squats or bends his back forward, he feels extreme back pain. This conditions his body to associate pain with squatting or bending forward. Thus, even after his initial injury heals, Jack’s body has learned that squatting or bending forward leads to pain. He now fears exercising his lower body as he doesn’t want to experience pain. Figure 2 illustrates how classical conditioning creates Jack’s fear of movement.

Fearing movement has been associated with greater disabling pain and poorer quality of life, something that we want to avoid as much as possible (Luque-Suarez et al., 2018). In essence, when it comes to lifters and injuries, it is paramount that we prevent this fear of movement from developing, while allowing for pain to guide our recovery.

So what do we do about pain?

Without going too much into detail, let us address the mindset we should adopt to cope with pain and injury, similar to what Jack had experienced (please seek a qualified healthcare professional if you are injured). When dealing with injuries, our thoughts and beliefs about the injury are important. Building mental resilience and being optimistic is the first step to recovery. The next thing is understanding that the intensity of pain experienced does not equate to the severity of the injury. As we have discussed in the BPS model, there are many factors that can contribute to one’s pain experience. Things like sleep, nutrition and stress and low-hanging fruit to address that can positively influence pain and recovery (Nevedal et al., 2013). Dwelling on pain hinders the time taken to recover. Instead, we should focus on what we can currently do. Noting down improvements in our ability to move while having a similar pain sensation can give us confidence that we are progressing in returning to normalcy. Slowly but surely, as we continue to move better and build positive momentum, the pain will subside as the body heals.

Conclusion

What I have covered is a brief overview of the current understanding of pain science, the development of chronic pain, Kinesiophobia, and the mental toughness we must strive to possess when we are injured.

Here are my main takeaways that I wish to impart to make you a more resilient lifter:

- The experience of pain is complex and we cannot blame the injury alone

- The amount of pain you experience does not equal the amount of harm done to your body

- Pain after an injury is a normal response to protect your body from further harm and serves to guide recovery

- Recognise that with most injuries, time will heal most wounds

- If you’re injured, focus on what you can do, rather than dwell on the pain

Thank you for taking the time to read this article about pain. I hope it has enlightened you on the complexity of this sensory and emotive experience that is very much a part of our everyday lives.

References

Barreto, R. P. G., Braman, J. P., Ludewig, P. M., Ribeiro, L. P., & Camargo, P. R. (2019). Bilateral magnetic resonance imaging findings in individuals with unilateral shoulder pain. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 28(9), 1699–1706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.001

Cordier, L., & Diers, M. (2018). Learning and Unlearning of Pain. Biomedicines, 6(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines6020067

Cormack, B. (2019, August 21). Have we ballsed up the BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL model? – Cor Kinetic. Cor Kinetic. https://cor-kinetic.com/have-we-ballsed-up-the-biopsychosocial-model/

Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Forsdyke, D., Smith, A., Jones, M., & Gledhill, A. (2016). Psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: a mixed studies systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(9), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094850

IASP. (2009). Global Year Against Musculoskeletal Pain. https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/MusculoskeletalPainFactSheets/AcutePain_Final.pdf

Luque-Suarez, A., Martinez-Calderon, J., & Falla, D. (2018). Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(9), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098673

Meulders, A. (2020). Fear in the context of pain: Lessons learned from 100 years of fear conditioning research. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 131, 103635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103635

Nevedal, D. C., Wang, C., Oberleitner, L., Schwartz, S., & Williams, A. M. (2013). Effects of an Individually Tailored Web-Based Chronic Pain Management Program on Pain Severity, Psychological Health, and Functioning. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(9), e201. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2296

Tonosu, J., Oka, H., Higashikawa, A., Okazaki, H., Tanaka, S., & Matsudaira, K. (2017). The associations between magnetic resonance imaging findings and low back pain: A 10-year longitudinal analysis. PLOS ONE, 12(11), e0188057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188057

Treede, R.-D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Finnerup, N. B., First, M. B., Giamberardino, M. A., Kaasa, S., Kosek, E., Lavand’homme, P., Nicholas, M., Perrot, S., Scholz, J., Schug, S., Smith, B. H., & Svensson, P. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160