This series of articles will be catered towards folks who have been lifting for a while and got their basics down. Here, we delve into the popular trend of arching in the bench press and break it down in an accessible format. Hopefully this would provide some insight and direction for your training!

What is arching and why do it?

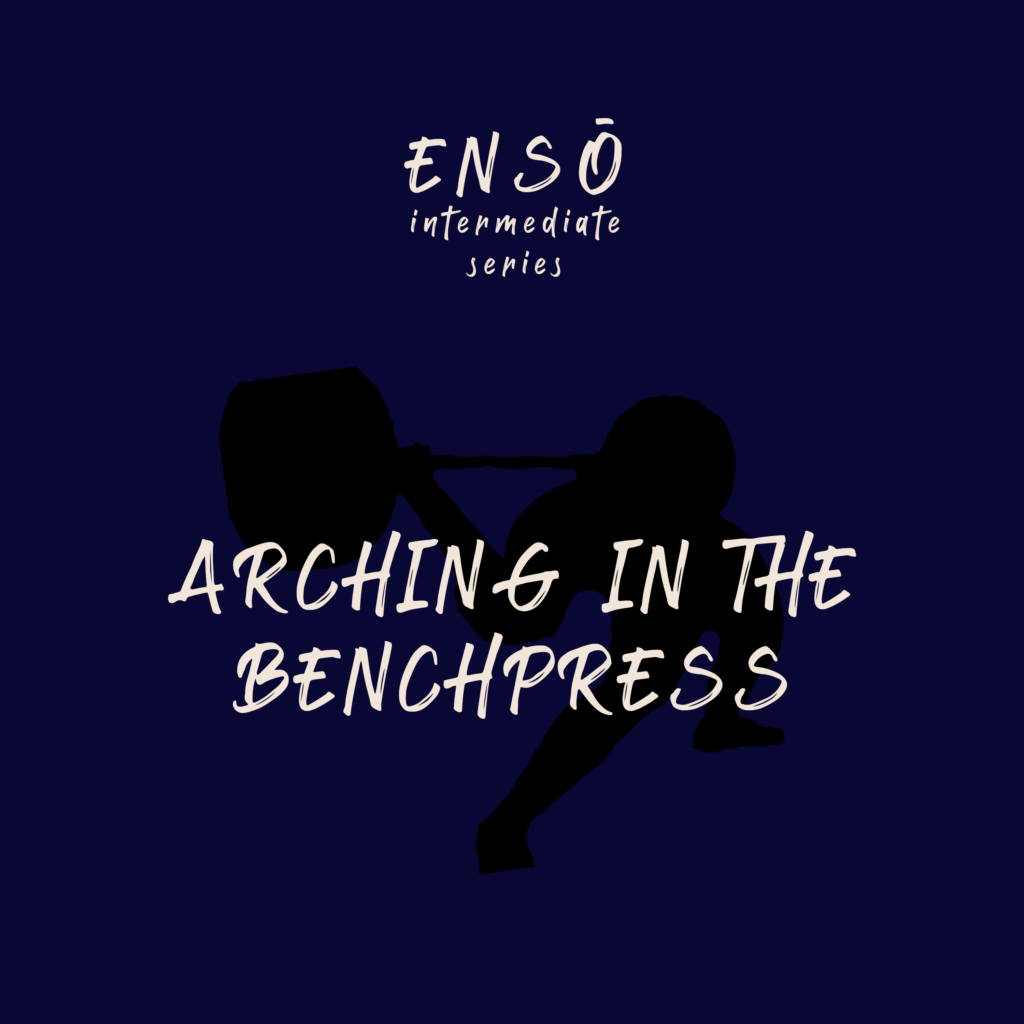

‘Arching’ is a setup used amongst powerlifters in the bench press where the lifter raises their chest and stomach towards the ceiling while keeping the back of the head, shoulders and glutes on the bench. Coupled here are the retraction and depression of the shoulder blades, and leg drive to maintain stability in the setup. Refer to our ENSŌ Beginner Series: The Bench Press article if you want to find out how to set up. Here is the result. Note the distance between the chest and the bar.

In a nutshell, powerlifters arch in the bench press as it is widely believed that it helps to increase performance. By reducing the distance between the bar and the torso, a shorter range of motion is achieved, allowing for heavier loads to be moved. It may also help orientate the fibres of the chest muscles for greater force production, though this is in large part related to the grip width used as well.

Are there specific studies on the bench arch?

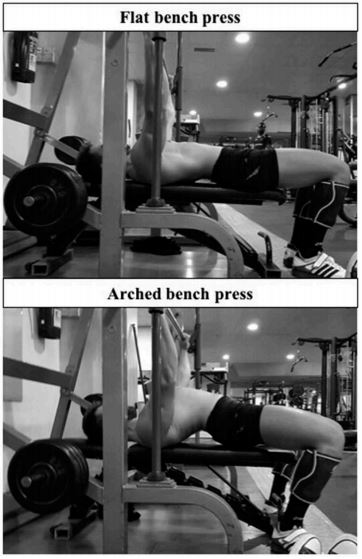

One study looked into the bench arch and found that there is no significant translation to better performance (García-Ramos et al, 2021), and that the arch did not significantly decrease the range of motion (mean differences of <2cm) amongst the 11 subjects.

This study might not sit right with a few folks, and indeed there was a follow-up commentary by Ribeiro Neto and colleagues on the small subject pool of 11 (2020), which can give rise to false positive results. They also suggested the further study of Para Powerlifters and their bench press techniques, as they similarly use the bench arch with their legs extended.

In the study, we also note that as the load increases, there was a corresponding increase in the range of motion. This indicates some collapse in the bench arch among the subjects, which could suggest that they are unfamiliar with the bench arch, or are possibly deferring to a less arched position which is stronger for them.

Furthermore, the bench arch is ill-defined in the study. The bench arch should stem primarily from the head, neck and upper body i.e. the cervicothoracic region. It’s why you might hear cues like “tuck in your chin” and “puff your chest out” in the bench press. Retraction of the shoulder blades is also intimately connected to the bench arch, an aspect that we should discuss in its own article.

Arching in the lumbar region also does not assist in reducing the range of motion as the bar lands on the chest and abdomen. Conversely, you can end up with some low back spasms and cramps trying to push the arch up in this region. The visuals of a high lumbar arch will naturally come with a sturdy upper body setup; the opposite is rarely true.

The range of motion (ROM) was also specifically examined in the bench press, in which a study found that a full ROM in Smith machine bench press training translates to better gains compared to partial ROM (Martínez-Cava et al., 2019). Greg Nuckols wrote an in-depth article on this study and its implications on the principle of specificity. This point is notable for powerlifters who employ techniques to reduce their ROM in competition. While they should still train with the competition-specific movement, these lifters should look into increasing the ROM in their variations/off-season training.

Not all that glitters is gold

Most people think about Eddie Berglund or Sean Noriega when it comes to impressive bench presses and their arches. The same can be said about fancier bench grip widths such as the ‘Japanese grip’. Bear in mind however, that these individuals tend to be the exception who can tolerate these positions well. While you can definitely experiment to find out if you belong within this category, manage your expectations and shoulders.

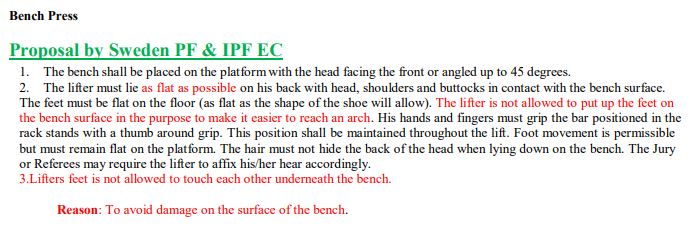

As a tangent, the rules favour the lower weight classes in maximizing their grip width and bench arch to move through the shortest range of motion. These positions are highly specific to the rules of the sport and do not always reflect the position in which a lifter produces the highest force. In fact, the issue of the bench grip width is currently being debated both within the scene and amongst some of the governing bodies of the sport.

What can you do?

1. Develop an arch

…that provides the necessary stability during the bench press and cap it there. Continuing to invest in the game of limiting ROM is unlikely to give you the gains you are looking for.

2. Get jacked

The more muscle you can pack on your frame, the higher your force production potential across all three lifts (Brechue & Abe, 2002). As highlighted above, moving through a full range of motion tends to give you better gains.

3. Develop your technique

Whether you’re a beginner or a veteran, getting better at the bench press and all its variants would likely be more fruitful in translating to your competition lift. A popular variation nowadays is to bench with the feet up to deemphasize the arch and leg drive.

4. Continue doing what works for you

If your bench press is going superbly and there are no nagging issues, there is little reason to drastically change your process.

Here are some local bench pressers who are strong across a wide spectrum of bench arches:

Also, here’s a snippet of bench performances on the international IPF stage.

Want to read more about the bench arch?

The Bench Press Arch — Is It Safe And Effective? by BarBend

The Bench Press Arch (How To Do It, Benefits, Is It Safe) by PowerliftingTechnique.com

Arching in the Bench Press: Please STFU by Juggernaut Training Systems

Fake Strength: Stop Arching the Bench Press by Tim Henriques on T-Nation

Conclusion

So.. to arch or not to arch? The answer is quite simple. At the end of the day, the goal in powerlifting is simply to lift the most amount of weight. Arching is simply a tool to help achieve a couple of things in the bench press:

- Orientate the fibres of the chest for greater recruitment in the movement

- Put your shoulders in a safer position

- Provide the necessary stability for greater force production

How much should you exaggerate the arch? That depends on you, as everybody is built different. Don’t be afraid to experiment and push the arch a little more. At the same time, acknowledge when it is counter-productive and hurting your ability to produce force.

Further questions? Feel free to contact us at [email protected].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jonus who gave insightful comments.

Special thanks to Jerome for granting us permission to use their videos. Hi Naz, please check your DMs :’)

References

Brechue, W. F., & Abe, T. (2002). The role of FFM accumulation and skeletal muscle architecture in powerlifting performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-001-0543-7

García-Ramos, A., Pérez-Castilla, A., Villar Macias, F. J., Latorre-Román, P., Párraga, J. A., & García-Pinillos, F. (2021). Differences in the one-repetition maximum and load-velocity profile between the flat and arched bench press in competitive powerlifters. Sports Biomechanics, 20(3), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2018.1544662

Martínez-Cava, A., Hernández-Belmonte, A., Courel-Ibáñez, J., Morán-Navarro, R., González-Badillo, J. J., & Pallarés, J. G. (2019). Bench Press at Full Range of Motion Produces Greater Neuromuscular Adaptations Than Partial Executions After Prolonged Resistance Training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003391

Ribeiro Neto, F., Dorneles, J. R., & Costa, R. R. G. (2020). Are the flat and arched bench press really similar? In Sports Biomechanics (pp. 1–2). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2020.1751872

Tungate, P. (2019). The Bench Press: A Comparison Between Flat-Back and Arched-Back Techniques. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 41(5), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1519/ssc.0000000000000494