Aleen Tan

Aleen Tan has been powerlifting for 6 years and competitively for 4. From a humble member of The Gym Nation, she has moved on to make numerous achievements in the sport under the guidance of Ronin Strength Co. Aleen is currently pursuing her Undergraduate Bachelor’s Honours degree in Physiotherapy from the University of Sydney, and will be graduating at the end of 2022. Her research project is dedicated towards women’s preferences for pelvic floor information to advise future awareness strategies. With many more Women’s Health project ideas, she looks to specialise in Women’s Health Physiotherapy and furthering her studies in the near future.

Editor’s note: As part of Aleen’s undergraduate research, women over 18 years are invited to complete a short study on pelvic floor health. Researchers at the University of Sydney are interested in what women know, if they want to know more, and how they’d like to receive this information. Data collection is still ongoing while you’re reading this, so feel free to click on this link to fill up the survey!

Perhaps you’re reading this article because you’re a female powerlifter who has experienced some sort of leaking while lifting. You could also be a coach reading this article to help address this issue for your female athletes. This article is targeted at the lay powerlifter, so medical jargon and expressions will be toned down. Even so, there are still some terms that I hope everyone will have a chance to learn to increase their knowledge in this area.

It is always helpful to have a disclaimer before proceeding. I am a student physiotherapist, not yet trained as a women’s physiotherapist. Most of my understanding about the pelvic floor comes from research and inference from available literature. If you are a keen follower of science in pursuit of greatness, references are available at the end of the article for your reading pleasure (if you’re met with a paywall do let me know).

What Is The Pelvic Floor?

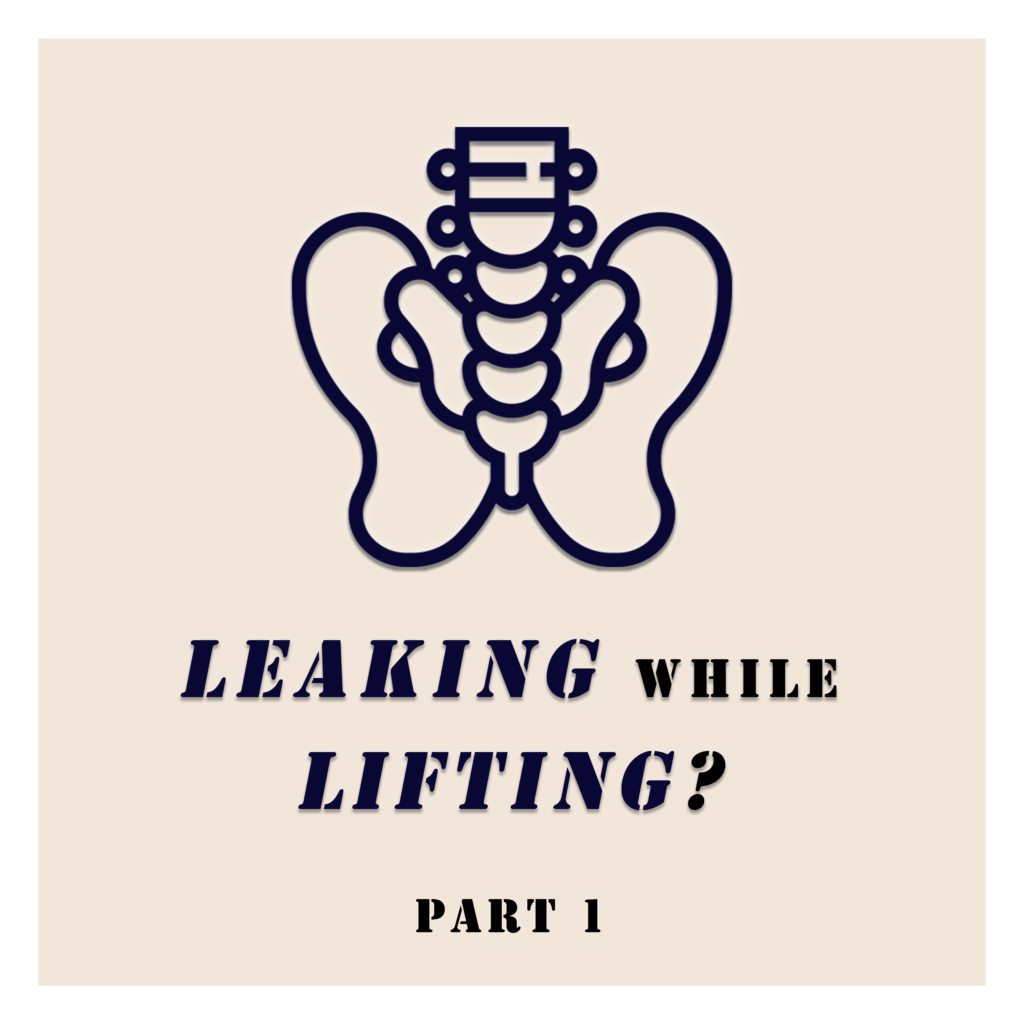

The pelvic floor is a hammock-shaped structure comprising muscles, ligaments and tissue [1]. This structure is located at the bottom of your hip to support the organs sitting within your hip bones. These organs include your bladder, womb and bowel; they are also termed as pelvic organs. The pelvic organs exit the body through your urethra (you can’t really find this when you look down), vagina (vulva is the part you see) and rectum (anus is the part you see), and are surrounded by the pelvic floor muscles.

What is The Function of The Pelvic Floor?

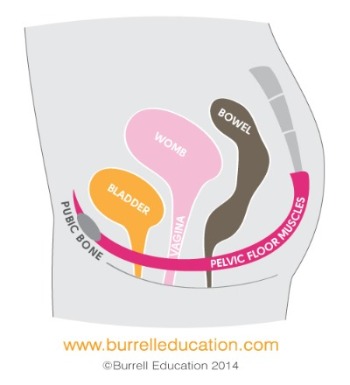

At rest, the pelvic floor muscles i.e. levator ani together with the urethral and anal sphincter muscles, which are composed of predominantly type 1 striated muscle fibres, maintain a constant muscle tone (constant muscle contraction) to keep the bladder and bowel exits closed [3]. This is one of the main reasons why we don’t walk around leaking pee and poop everywhere.

Thus, the pelvic floor helps you to control your need to pee, hold your pee when you are coughing or jumping, hold your fart/poop in public, force your pee/shit out when you are in a hurry (not ideal, please stop doing this, I’m watching you) and reach sexual arousal/orgasm.

Why is it bad to force your pee/shit out when you are in a hurry?

This action is called “straining”. When you strain, you are directly applying pressure on your bladder and bowel to excrete your pee and poo. When this has been practiced for prolonged periods, one would grow accustomed to the sensation and strain when asked to contract the pelvic floor. Also, given the amount of practice straining, these women would be prone to strain at times of high IAP and experience leakage.

An advice I would give regarding this is to fully relax when you have to go. Also, do not disrupt the urine stream like how most instructions to contract the pelvic floor are given. This may disrupt the fine neurological balance to complete urinating.

So how should I contract the Pelvic Floor?

Let’s first try locating the pelvic floor in you. If you take your hand and slide it down from your belly button, you’ll reach a bony point, this is your pubic symphysis (sim-firh-sis). Then, slide your finger down your butt crack and you’ll feel your tailbone, this is your coccyx (kok-six). For the third and fourth points, sit on a hard surface and lean your body slightly sideways. You will feel the bones underneath your butt cheeks, which are your ischial (Eee-sh-iel) tuberosities. These are the four points that your pelvic floor attaches like a hammock horizontally to support your pelvic organs.

You’ll need to focus on directing your efforts down south. You can do this by sitting on a chair with a back rest or lying down on the floor with your knees bent. Relax in that position by closing your eyes and concentrating on the region by paying attention to the blood flow, temperature and the feeling of clothes against your skin. Bringing your attention to the vagina, think of closing the entrance of the vagina and lifting it up. You shouldn’t be feeling as if your stomach is pushing down onto your pelvic floor and the glutes, quads, hamstrings and abs should remain relaxed.

- Sucking a blueberry into your vagina

- Bringing your anus closer to your vagina

- Plucking a tissue with your vagina

- Trying to stop your fart in public

For more information, please visit thepelvicfloorproject.com.

What Happens When the Pelvic Floor can't function properly?

Leaking of urine is called urinary incontinence (UI) and there are two main subtypes: Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) and Urge Urinary Incontinence (UUI) [2].

Stress Urinary Incontinence refers to the complaint of urine leakage in association with coughing, sneezing or physical exertion, whereas Urgency Urinary Incontinence is the complaint of urine leakage associated with a sudden compelling desire to void that is difficult to defer. These are the symptoms of the conditions as described by the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and the International Continence Society (ICS) standard definition [1].

Can UI be cured?

This will depend on the diagnosis. There are many types of leaking that a person can experience based on the activities they do and the symptoms they have.

Generally, urinary incontinence can be treated with conservative treatment methods i.e. requiring no surgery or hospital stay [6]. Conservative treatments include: bladder training (relearning voiding habits), diet management (caffeine and water intake), exercise regimen (proper rest and exercise intensities) and pelvic floor muscle training (contracting the pelvic floor) for example [7]. More details on these treatment methods will be discussed in the next few parts of the article.

Will UI lead to long-term health concerns?

Data is currently insufficient to determine whether strenuous activities such as powerlifting or resistance training while young predisposes the individual to pelvic floor disorders later in life [8].

Among studies that are available, it is shown that elite athletes—including Olympians—do not experience increased SUI even 15-20 years after their prime. However, they may experience UI earlier in life.

My stance is that it is hard to determine whether a person will experience worse symptoms in the future. Many studies have proven a strong association between pelvic floor symptoms with increased age. It is inevitable that we will experience such symptoms as we age, and some of us may suffer from more severe symptoms. For instance, approximately 50% of elderly women suffer from one or more PFD symptoms.

How Common is SUI? Is It More COmmon Among Middle Aged Women? Can It Affect Younger Women?

Common pelvic floor dysfunctions including urinary incontinence can affect women at all stages of life. From as young as 14 years old to >90 years old [9,10]. In adolescence, prevalence is low at approximately 10% while for older women >50 years can be as high as 50% (which is half of all women) [11,9].

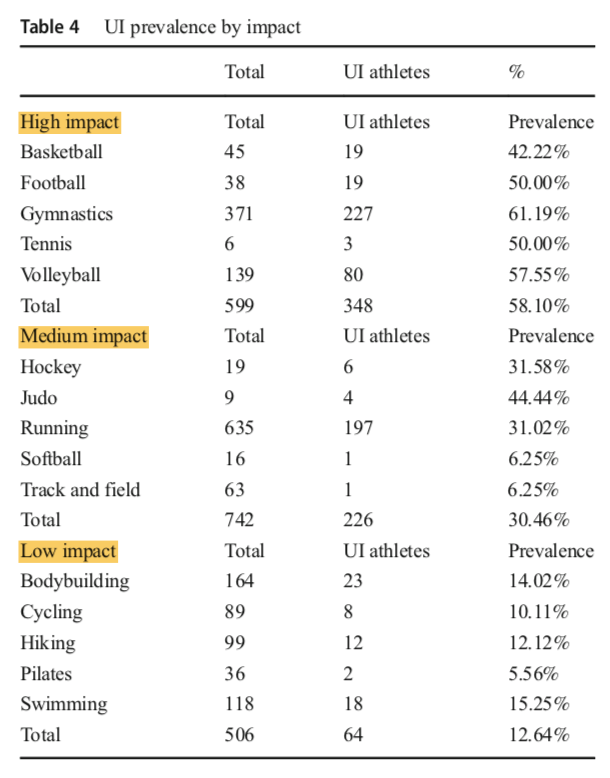

Among female athletes, occurrence rates have proven to be high amongst female athletes in high impact sports like gymnastics, volleyball, soccer and trampolinists [12-14]. In a recent systematic review, categorization of subjects according to sports impact revealed a positive correlation with urinary incontinence [14]. Generally, high impact sports showed a higher prevalence than low impact sports.

What Are The Risk Factors Commonly Associated with SUI?

Modifiable risk factors are variables that can be modified to manage symptoms of SUI. These include lack of exercise [15] and its contrast, strenuous sporting activities [16]. High physical stress is placed on the pelvic floor when the individual is overweight/obese or suffers from chronic cough [15,17,18]. High emotional stresses and anxiety problems contribute to the issue as well [19-21]. Moreover, soreness and injury in the hip and lower back muscles may affect the function of the pelvic floor too, given that muscle activations during movement don’t happen in isolation [12,22,23].

On the other hand, there are also several unmodifiable factors: increasing age [24], having one or more children (termed as parity) [15,17,24] and existing comorbidities like hypertension and diabetes [15,20].

So do Sports and Exercise Help with SUI?

As a Weightlifter, is this normal or is there something wrong with me?

Let’s define what is normal and what is abnormal. ‘Normal’ in the medical world can mean that a particular condition has a cause which can be eliminated or changed to reduce the impact of the effect. ‘Abnormal’ refers to issues that require medical attention and a greater level of monitoring and treatment methods.

With that in mind, let’s go through some examples first. Acne outbreak is not usually normal. However, in a teenager undergoing puberty, it is normal. Lower back soreness (pain in simpler terms by most people) is normal the day after some intense high volume deadlifts. There is a certain cause for a certain effect. With proper lifestyle adjustments, off-the-shelf acne products, and modifying your training, these problems can be tackled easily.

Applying this perspective, diagnosis of a leaking problem has multiple levels. It depends on the severity and trigger threshold of the leaking problem to decide the level of intervention, ranging from adjusting factors around, to seeking direct medical attention. Occasional leaking while doing strenuous activities with high IAP on the pelvic floor is a common symptom experienced by many. Female athletes are approximately three times more likely to have urinary incontinence compared to control groups [16].

However, it is not normal if you are experiencing worsening symptoms within a short period of time where you are experiencing streams of leakage (one training cycle), doing only 50-60% of your max at low volumes and that you feel like there is a bulge in your down south. A red flag is when you start experiencing leaking during daily activities like hanging laundry, washing clothes, cooking and coughing or sneezing, where these symptoms did not exist before. If you are experiencing any one of these symptoms, I’d advise you to visit your healthcare professional, preferably a trusted women’s physiotherapist.

If you are experiencing incontinence due to a recent increase in training volume and high caffeine/water intake due to water loading, I would say that there is a cause and effect. Drinking too much water will result in higher bladder pressure and a simple intervention is to practice proper voiding habits before training. Relax entirely to finish voiding and to not strain when urinating (forcing your pee out). Another solution is to limit the use of caffeine and adopt better habits to increase daily energy levels like increasing sleep time and better food choices. As for training regime, I’d advise you to talk to your coach to work out a better more gradual training progression to suit your body’s recovery needs.

I understand that it may be difficult to change many different factors e.g. to lose weight and hit high training numbers. It would be prudent to work out a more effective plan in the long term to meet your training goals.

Does Powerlifting Result in Increased Stresses on The Pelvic Floor?

- Only use the belt when you really need to.

- Employ a more gradual progress in your lifts rather than having a chiong sua attitude.

- Learn to breathe and brace. There is no need to belt up so tightly that you can’t brace properly.

- Learn how to co-contract your pelvic floor during a lift.

How Common is SUI in Powerlifting? What are the Other Risk Factors?

Powerlifting is a low impact sport with low ground reaction forces [16]. In a recent study amongst 134 female powerlifters in Australia [25], 41% experienced SUI at some point in time, while 37% were experiencing SUI during training, competition, or maximum effort lifts. This is an alarming rate which calls for more attention!

In the same study, the researchers studied the effect of age, body mass, resistance training experience, and competition grade on the incidence of UI. They found that the incidence of UI was ONLY significantly different among women with different resistance training experience compared to other factors like age groups, body weight categories, or competition grade (come chat with me if you want to find out more). The last item in their questionnaire asked for women to list down comments on their experience with UI in powerlifting and 27 women out of 134 replied. This is a very small number of participants but it may be worth looking at what these women have said.

UI in training: deadlifts have resulted in increased incidences of UI with sumo resulting in more UI than conventional. Following deadlifts are squats and front squats. A handful reported that wearing a belt caused UI.

Intensity vs volume: UI often happens with very heavy or maximal weights while some commented that UI happened at the end of sets with moderate to heavy weights. One woman indicated that the weight that triggered UI increased progressively as her strength increased. This aspect is highly subjective and one should be aware that “heaviness” is perceived differently by every individual.

It Seems like most of the time, UI happens with women who pull sumo. Are they at greater risk than those who pull conventional?

As per the findings from Wikander et al. [25], women who pull sumo seem to be at higher risk. There were no further discussions regarding this and reasons behind that will only be more conclusive after more investigations are done.

I speculate that with the position of the torso angled more perpendicular to the ground, perhaps there is a biomechanical association between vertical forces acting directly on the horizontal hammock structure of the pelvic floor and the higher incidences of UI during sumo. Future research can look into the different types of lifts that cause higher incidences of leaking to have a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Wrapping Things Up?

Understanding of urinary incontinence in powerlifting is at its infancy. At this stage, we understand that many women start to experience urinary incontinence after starting powerlifting and that there are several risk factors that may increase the odds of these women experiencing UI. Moreover, we also have mental health and soreness/pain in the pelvic region to think about. In the next part of the article, we will discuss the different types of rehabilitation protocols used for SUI and strategies, including specific exercises for the pelvic floor, that may help with SUI symptoms.

If you’ve experienced incontinence during your time powerlifting, do you agree with this? Let us know in the forums. You may also contact me here!

References

1. Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, Bø K, Corcos J, Fowler C, Laycock J, Lim PHC, Van Lunsen R, Lycklama Á Nijeholt G, Pemberton J, Wang A, Watier A, Van Kerrebroeck P (2005) Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: Report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the international continence society. Neurourology & Urodynamics 24 (4):374-380. doi:10.1002/nau.20144

2. Yoshitaka A, Heidi WB, Linda B, Jean Nicolas C, Daly JO, Rufus C (2017) Urinary incontinence in women. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 3 (1). doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.42

3. Ashton-Miller JA, Howard D, Delancey JOL (2001) The functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor and stress continence control system. Scandinavian Journal of Urology & Nephrology 35 (207):1-7. doi:10.1080/003655901750174773

4. Vodušek DB (2015) Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of pelvic floor muscles. In: Bo K, Gehrmans B, Morkved S, Van Kampen M (eds) Evidence-based physical therapy for the pelvic floor: Bridging science and clinical practice. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, United Kingdom.

5. Bump RC, Norton PA (1998) Epidemiology and natural history of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstetrics & Gynecology Clinics of North America 25 (4):723-746. doi:10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70039-5

6. Bø K (2012) Pelvic floor muscle training in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and sexual dysfunction. World Journal of Urology 30 (4):437-443. doi:10.1007/s00345-011-0779-8

7. Bo K, Gerhmans B, Morkved S, Van Kampen M (2015) Evidence-based physical therapy for the pelvic floor: Bridging science and clinical practice. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, United Kingdom

8. Nygaard IE, Shaw JM (2016) Physical activity and the pelvic floor. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 214 (2):164-171. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.067

9. Zeleke BM, Bell RJ, Billah B, Davis SR (2016) Symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling older Australian women. Maturitas 85:34-41. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.012

10. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ (2008) Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Journal of the American Medical Association 300 (11):1311-1316. doi:10.1001/jama.300.11.1311

11. Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland AD (2014) Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstetrics & Gynecology 123 (1):141-148. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057

12. Casey EK, Temme K (2017) Pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence in the female athlete. Phys Sportsmed 45 (4):399-407. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2017.1372677

13. Eliasson K, Edner A, Mattsson E (2008) Urinary incontinence in very young and mostly nulliparous women with a history of regular organised high-impact trampoline training: occurrence and risk factors. International Urogynecology Journal 19 (5):687-696. doi:10.1007/s00192-007-0508-4

14. de Mattos Lourenco TR, Matsuoka PK, Baracat EC, Haddad JM (2018) Urinary incontinence in female athletes: A systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal 29 (12):1757-1763

15. Zhu L, Lang J, Wang H, Han S, Huang J (2008) The prevalence of and potential risk factors for female urinary incontinence in Beijing, China. Menopause 15 (3):566-569. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31816054ac

16. Bø K, Nygaard IE (2019) Is Physical activity good or bad for the female pelvic floor? A narrative review. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01243-1

17. Stothers L, Friedman B (2011) Risk factors for the development of stress urinary incontinence in women. Current Urology Reports 12 (5):363-369. doi:10.1007/s11934-011-0215-z

18. Hrisanfow E, Hägglund D (2011) The prevalence of urinary incontinence among women and men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Sweden. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20 (13-14):1895-1905. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03660.x

19. Vigod SN, Stewart DE (2006) Major depression in female urinary incontinence. Psychosomatics 47 (2):147-151. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.147

20. Siddiqui NY, Wiseman JB, Cella D, Bradley CS, Lai HH, Helmuth ME, Smith AR, Griffith JW, Amundsen CL, Kenton KS, Clemens JQ, Kreder KJ, Merion RM, Kirkali Z, Kusek JW, Cameron AP (2018) Mental health, sleep and physical function in treatment seeking women with urinary incontinence. The Journal of Urology 200 (4):848-855. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.04.076

21. Choi EPH, Lam CLK, Chin WY (2016) Mental health of Chinese primary care patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Psychology, Health & Medicine 21 (1):113-127. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1032309

22. Pool-Goudzwaard A, Slieker ten Hove M, Vierhout M, Mulder P, Pool J, Snijders C, Stoeckart R (2005) Relations between pregnancy-related low back pain, pelvic floor activity and pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal 16 (6):468-474. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1292-7

23. Cassidy T, Fortin A, Kaczmer S, Shumaker J, Szeto J, Madill S (2017) Relationship between back pain and urinary incontinence in the Canadian population. Physical Therapy 97 (4):449-454. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx020

24. Zhu L, Lang J, Liu C, Han S, Huang J, Li X (2009) The epidemiological study of women with urinary incontinence and risk factors for stress urinary incontinence in China. Menopause 16 (4):831-836. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181967b5d

25. Wikander L, Cross D, Gahreman DE (2019) Prevalence of urinary incontinence in women powerlifters: A pilot study. International urogynecology journal 30 (12):2031-2039