JONATHAN CHUA

Jonathan Chua is a caffeine addict and coke zero connoisseur, who enjoys analysing and reviewing research articles on athletes’ performance in sports. He graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Sport & Exercise Science back in 2019. Jonathan has been powerlifting since 2014, and he slowly began his coaching journey shortly after. He was the co-founder of Prime Athleticus, and is currently one of the coaches of The Strength Guys.

introduction

There are various ways you can prepare for a meet, and there are no one-size-fits-all programmes that will allow everyone to perform their best on meet day. However, there are certainly some important aspects that you can take note of. In today’s article, we will highlight the following:

1. What is periodisation and programming? How does it work to improve our strength and allow us to perform at our stronger on a given day (meet day), and why are they important?

2. How do we plan our programming leading up to the meet?

a. What structure should the program take?

b. How do we understand and utilise the data gathered from your training?

c. How do we measure our improvements through the training period?

d. How do we plan it in the long-term?

what is periodisation?

Periodisation refers to the changes of Volume, Intensity, and Frequency over time to optimise performance for competition. All 3 elements are important metrics for us to track and they also influence the type of training adaptation that is introduced. You want to make sure that the type of adaptation fits the objectives of your training program. For example, if you are doing low intensity (e.g., 40 to 50% of your 1 RM) at very high repetition sets (20 to 30 reps), you may build up a lot of endurance, but it is not the most productive or optimal in terms of expressing your strength in a 1 RM.

There are multiple types of periodisation and each of them can serve as guidance to help you plan towards your objectives.

Linear Periodisation

Linear periodisation refers to a type of training where volume starts at the highest, and intensity starts at the lowest. Through the training cycle, your intensity picks up to the highest, while the volume drops to the lowest at the end.

Reverse Linear Periodisation

Just like linear periodisation, but volume starts at the lowest, and intensity starts at the highest. Through the training cycle, your intensity drops to the lowest, and volume picks up to the highest at the end.

Undulating Periodisation

Undulating periodisation refers to a type of training where the intensity and volume goes up and down (undulates) either session to session, or weekly. This is what we do most of the time, and a lot of programmes incorporate this.

Block Periodisation

Refers to a type of training where each training block specifically trains one type of stimulus and aims for one type of improvement. For example, Power, Strength, Hypertrophy, etc.

Planning your Programming

Your programming is a framework to help navigate towards your end goal. Since we are talking in context of a meet prep here, it will be to perform your 1 RM on a given day. Your programming incorporates these various types of periodisation to a certain degree (it is not only one type or the other, there will always be some overlap) and there are truly countless ways to how you can incorporate these elements to structure your program to meet your objectives. So why are they important? Programming can guide us in the planning to perform our best on the meet day. Like a roadmap, it improves our navigation process and directs us in the right direction. In doing so, we can also figure out what works and what does not.

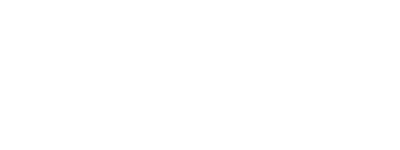

In the diagram below, you can see an illustration of a theoretical assumption on how adaptation occurs over time.

1. Overload — When training occurs and our body experiences stimulus, it “shocks” our body.

2. Alarm Adaptation into Plateau — The stimulus brings about an adaptation to prepare our body for whenever the training stimulus comes again.

a. The plateau could also be an indication that you might be doing too much too soon, such that you are not able to see the benefits of the training that you have done so far. If you continue to add more, it will lead to overreaching, and eventually overtraining.

Illustration adapted from Mike C Zourdos on General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)

Training is a continuous process that evolves over time based on your own schedule, goals, training data, assessment, improvements, and athlete well-being (psychologically and physiologically). It is important to structure your training in a way that is engaging and productive towards your goals. Every individual adapts and recovers at different rates, and external factors such as your work or school stressors, lifestyle, nutrition, sleep, etc. affects them. As such, you have to plan your training with these factors in mind in order to suit your schedule, lifestyle and goals to sustain long-term progression. Something that people might overlook is the adherence and state of mind of the athlete coming into the sessions. When the program is monotonous and athletes feel bored, the efficacy of the program can decrease significantly, not to mention voluntary force production (INTENT) during the session itself will be hugely affected.

structure

Typically, your programming takes the form of a macrocycle, which consists of blocks of mesocycle, which consists of microcycles.

Macrocycle

Macrocycles are the broad training period which ranges from 12 to 20 weeks. For powerlifting, the end of a macrocycle usually follows a competition or a mock meet. The duration of the macrocycle depends on the given timeframe that you have or the lifter’s training age.

Macrocycle helps us set an end goal, which helps to facilitate the planning of the mesocycle (such as the volume and intensity) in order to improve performance.

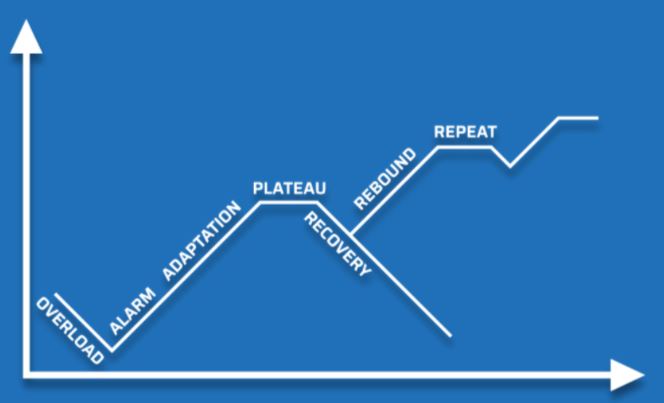

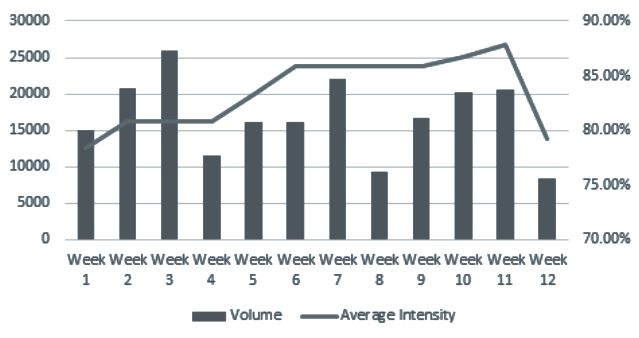

Example of a Macrocycle. Each bar represents the total volume done in a Microcycle.

The line represents e1RM through the Macrocycle.

Mesocycle

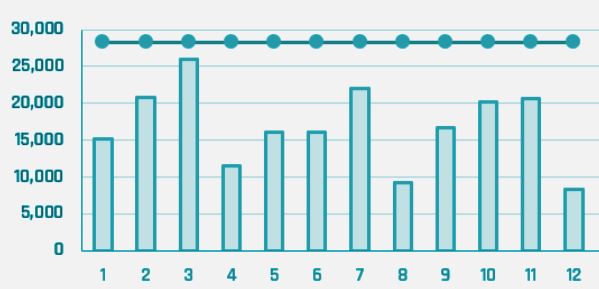

Mesocycles are building blocks that make up the Macrocycle. They are a group of consecutive training weeks (microcycles) that are focused on training the same skill or physical quality (E.g., strength, hypertrophy, power, etc.).

Each mesocycles has its own set of objectives as depicted in the diagram as an example.

Examples of how Mesocycles are broken down, with its own sets of objective.

Microcycle

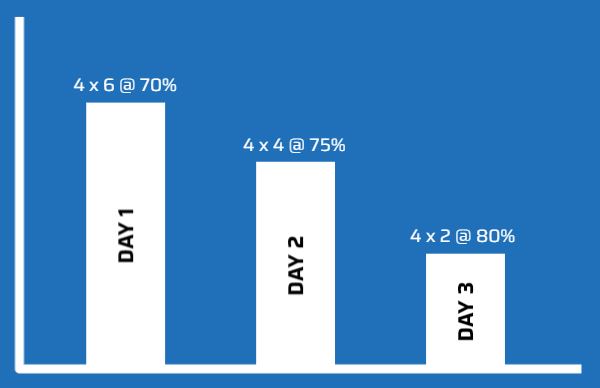

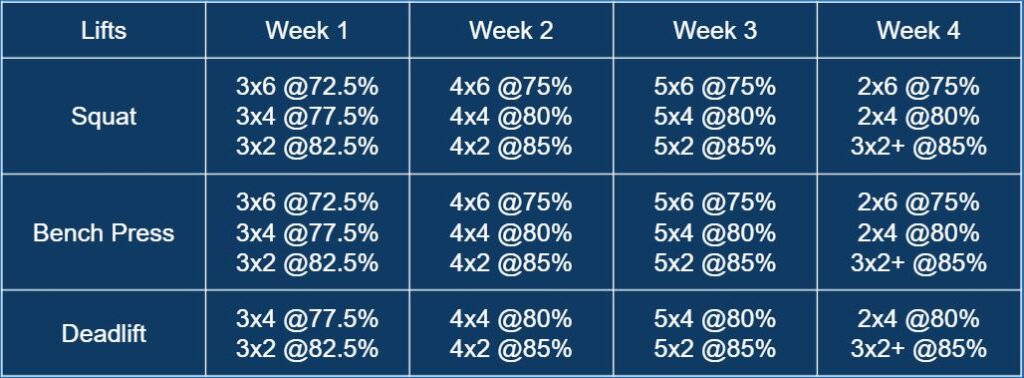

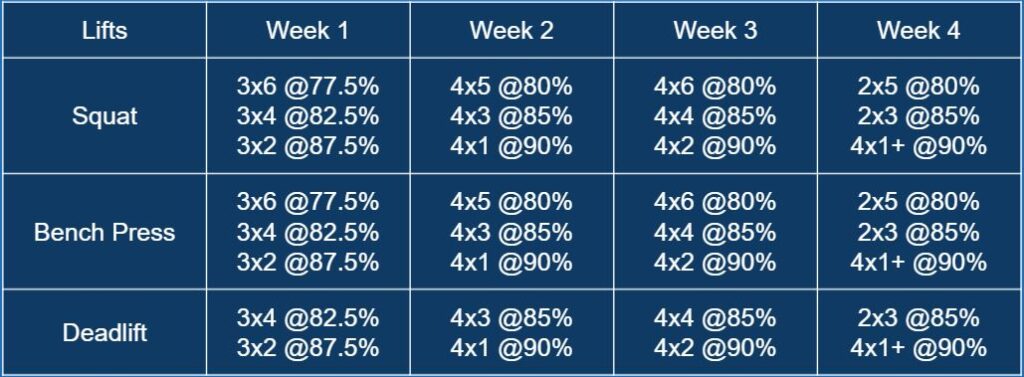

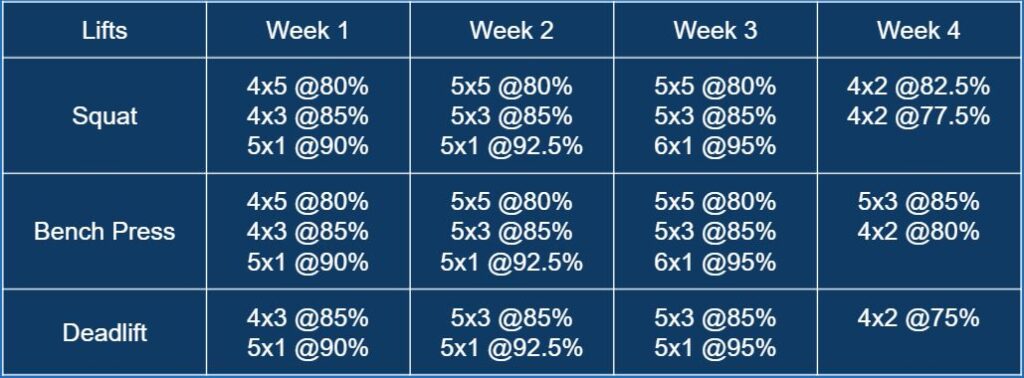

The weeks that make up mesocycles. There are different ways to structure your weeks, but the most common method would be to incorporate Daily Undulating Periodisation (DUP), which varies the intensities and repetition ranges on the different training days of the week. DUP allows the lifter to be exposed to the different physical qualities in the same week. I.e., hypertrophy, strength, power.

E.g. Day 1: 4 × 6 @ 70%, 4 × 4 @ 75%, 4 × 2 @ 80%

Example of DUP in a Microcycle

Understanding the data

To understand the data, you have to know the metrics that you are training in terms of your training. The 2 most fundamental metrics that you can track are Training Volume and Average Intensities.

1. Training volume: total workload a lifter has done during a given time. Usually tracked in workload done per week. Calculated by LOAD X REPS X SETS. Each individual lift (S/B/D) will have its own volume threshold.

2. Average intensities: Intensity that was performed during a given time. Usually tracked in average intensity for the week as well.

With the data collected, we have to observe, compare, analyse, and communicate it accordingly to the lifter to let them understand what is working and what is not. That way, you can slowly work towards finding the “optimal training dose” by taking into account the lifter’s external stressors such as exams, busy work periods, big life changes, etc. and also looking at the training metrics as a whole. Grinding the lifter hard during stressful periods of their life might potentially negatively affect the lifter’s confidence and performance in the gym, even if they can complete their training as prescribed. Dropping their overall training volume might even be more beneficial as they will then be able to manage the training load better and recover well session to session. You want to progressively overload the training dose but at the same time, you have to recognise that the “optimal training dose” will be different at different points of time.

It is important to note that you should closely analyse the improvements of the competition lifts over time as well. With compound movements like SBD, you have to train them as if you are executing them in a competition and get used to the movement pattern to improve your strength level. Strength expression can come from multiple factors: mobility level, stress level, coordination level, recovery rates — they will impact the way you move. If you are performing variations of the competition movements, they may not guide you to perform the same type of coordination and execution as the competition lifts. You may incorporate variations when there are specific weaknesses that the variation can directly address. However, if there are not any, or for people who are just starting out, drilling down the competition lifts might be the most productive, and you can see significant progression from there.

Total Volume done vs Average Intensity of competition lifts over time.

measurement of improvement

While analysing the data, it is important to know how to recognise that you ran successful training blocks. To measure the improvements, you can incorporate various types of assessments at the end of the training block, which can be broadly categorised into Process-oriented Assessment and Outcome-oriented Assessment.

Outcome-oriented Assessment

Typically, Outcome-oriented Assessments are used rather sparingly as you need to put the lifter in a peaking cycle/competition phase, which usually affects the subsequent weeks of training following that because of how hard you push in that given session. Outcome-oriented Assessments include Competition Results, and Direct 1 RM Assessment.

Process-oriented Assessment

Process-oriented Assessment can be used at the end of the training block, but they can be observed throughout the block as well. Process-oriented Assessments include RPE Gauge, Velocity Changes, AMRAPs, and Video Analysis.

RPE Gauge

You can observe how the RPE of a given lift progresses given the same weight (e.g., 140kg @ 8 → 140kg @ 7), or increase in weight of a given RPE (e.g., 150kg @ 8 → 160kg @ 8). It can be used in training in a form of top singles at a given RPE, RPEs of working sets, fatigue singles (how fast they fatigue down during the training session itself).

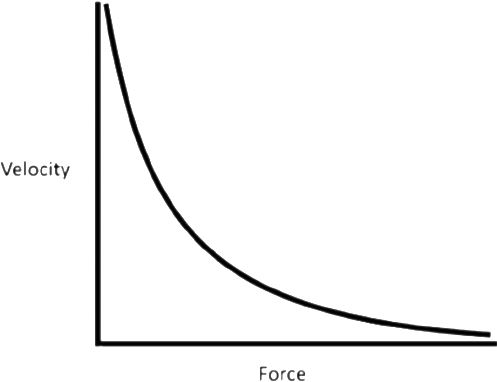

Velocity Changes

You may track how the velocity of a given weight changes through the block. E.g., 140kg @ 0.16 m/s to 140kg @ 0.22 m/s. However, you need a velocity tracker/linear transducer to be attached to the barbell to obtain this data. Data to be recorded are mean concentric velocity (MV), load, and the minimum velocity threshold (MVT) on the last repetition on each set (the slowest speed that you can grind up to).

Velocity-Force Curve

AMRAPs

You can see whether the lifter can perform more reps of a given weight compared to before. E.g., 150kg x 8 @ 10 at the end of the block vs 150kg x 5 @ 10 from the previous block. Usually done after a working set. However, to not tax too much, it is used rather sparingly, or used with an RPE or repetition cap. From there, you can see the increments or decrements of e1RM based on the number of reps performed. You should use the RPE table for reference as well. Records of AMRAP should be recorded to give a better insight into training adaptations across the phase. With the record, you can see whether that particular training structure in that given period works well for the lifter or not.

Video Analysis

From video analysis, you can observe any visible technique improvements of the lifters. To a certain extent, you can assess how far and well the lifter moves a certain weight as well compared to the previous time the lifter executed the same weight.

long-term planning

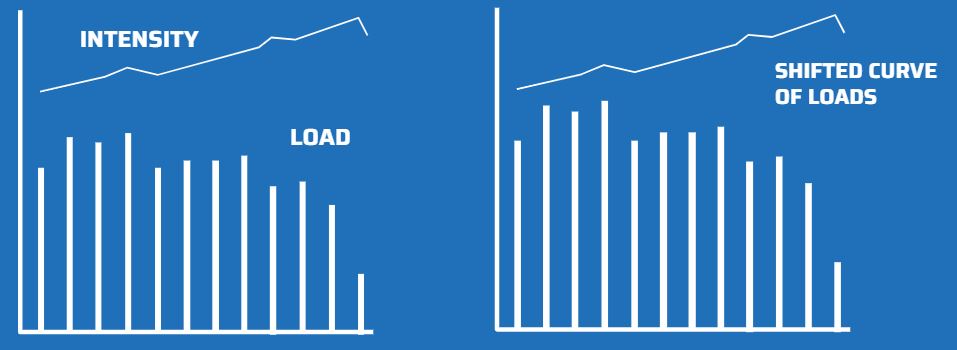

Training should be scalable over time. In The Strength Guys, we address this as Shifting the Curve. To shift the curve, the lifter must be able to progress to a new Peak Volume across many average intensity points. Over time, the overall training volume should be scaled higher than before. For example, at 75% average intensity, you have done 10,000kg in total volume, and at 80% average intensity you have done 5,000kg in total volume. Over time, you want to bring the total volume at each average intensity to a higher point, such as 12,000 and 6,000 respectively.

Shifting the Curve – Training volume scaled higher compared to before given the same average intensity

Here are some of the considerations that you may take for long-term planning as well:

1. more is not always better for injury reduction

Previously, there was a saying that “Volume is King”. A lot of people might be doing too much volume too soon. A few examples would include the Smolov squat/bench program. While you may adapt quickly in the short term, you might see your performance decreasing because you cannot sustain the amount of progression over that long period of time, and your recovery is not able to catch up.

2. training at peak volume increases the risk of injury

You want to push for new peak volumes, but you have to consider the greater risk as well given the greater amount of load.

3. increments of volume week to week should kept within 5 to 15% to reduce risk of injury

To manage the load increment and injury risk from repetitive movements and loading towards the soft tissues (joints, muscles)

4. once peak volume is achieve without any injury, it can be good data to compare across all training weeks

Over time, you want to slowly build your peak volume to a higher threshold. There is no exact time frame to when you need to beat that peak volume. Slowly build the load up over time so that your body can be better prepared to handle the higher training load.

further considerations when increasing workload:

1. When should we aim to hit peak volume?

Usually, you hit peak volume at the earlier phase (Preparatory Phase). Intensity is not at the highest and it is usually easier to hit peak volume. Peak volume usually happens right before a deload, but it still depends on the lifter’s age. For more experienced, elite lifters, peak volume can be maintained for several weeks before a deload week. For newer lifters, usually just a week or maybe two before deloading to avoid experiencing symptoms such as nagging joint or muscle aches, which will affect your coordination and overall performance.

2. How long of a macrocycle does the lifter need to prepare for the workload?

Highly dependent on the training age of the lifter. For newer lifters, typically adaptations occur quickly and you might not even need to periodise your training. It highly depends on the mesocycle duration as well, which can vary from 4 to 8 weeks.

3. When should we increase training frequency?

You can consider increasing your training frequency when you have to do too much in a given session. Doing too much in a given session might put you in a recovery debt, and also force you to spend a lot more time in the gym, which is not something everyone has time for. Increasing your frequency can help to spread your volume throughout the week, so that each session is not too taxing for the lifter to recover. Additionally, it can give the lifter more opportunity to practice the lift more in a week, and help to develop their skills in performing the lift.

4. Which measurement method should be used at different time point?

Make sure that the lifter is actually prepared to do the particular assessment. For example, AMRAP can be used in the Preparatory Phase and Development Phase, but not usually for the Competition Phase because of the intensity demand in the Competition Phase. On the flip side, RPE assessment (E.g. RPE 9 singles) might not be a good idea to be used in the Preparatory Phase and Development Phase because of how big the intensity jump has to be.

5. If an injury occur, is it from the high workload or is it a workload that the lifter is not prepared for?

Metrics come into play here, where you can have an objective insight to what the lifters are actually capable of doing. Were the load increments week to week intense? Has the lifter done this workload before and were completely fine before? Did the lifter go through any big life stressors lately? Or any lifestyle changes? These considerations might help you. Above all, the coach and athlete have to communicate so that they both have complete understanding, and ask the correct questions to find out the factors influencing the injuries or pain.

conclusion

When crafting your own training, it is important to do so with data metrics. The more data that you can collect, the more information you have to help guide you on your decision-making process. While metrics may not be the end-all-be-all, keeping track of your training metrics is extremely important to make sound decisions. To tie everything together, here is an example of how you can structure a meet preparation:

The Preparatory Phase: Build the lifter’s foundation and work capacity by easing them into increased training volume. Ends the mesocycle with an assessment in the form of an AMRAP.

The Competition Phase: Specific intensities that are utilised in competition. A reduction in training volume on the week of competition.

Further questions? Feel free to contact us at enso.powerlifting@gmail.com.